Chinese authorities have declared the work of He Jiankui, a scientist who claims to have created the world’s first gene-edited babies, a violation of Chinese law and called for the suspension of all related activity.

“The genetically edited infant incident reported by media blatantly violated China’s relevant laws and regulations. It has also violated the ethical bottom line that the academic community adheres to. It is shocking and unacceptable,” Xu Nanping, a vice-minister for science and technology, told the state-owned CCTV on Thursday.

Xu called for the suspension of any scientific or technological activities by those involved in He’s work.

The Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, where He is an associate professor, has said it had no knowledge of his research.

The scientist has said his project was approved by an ethics committee at Harmonicare Shenzhen women and children’s hospital, which has also denied any involvement.

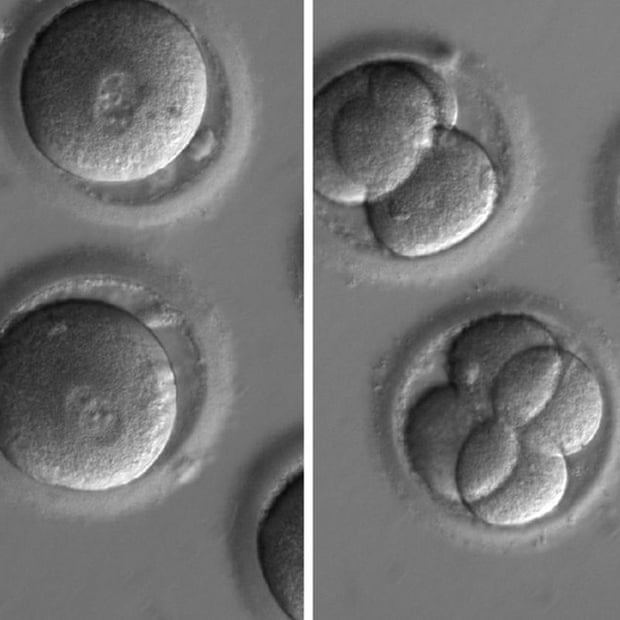

He shocked the global scientific community when he claimed this week to have edited the genes of embryos that resulted in the birth of twin girls named Lulu and Nana.

However, his work – a byproduct of personal ambition and a vague regulatory environment in a country that has been pushing ahead in the field of gene editing for years – did not come as a total surprise to everyone.

William Hurlbut, a bioethicist at Stanford University who has been in touch with He since an ethics conference last year, said: “I knew that was his long-term goal. I just didn’t think he would push so imprudently. I worried his enthusiasm for what he was doing was so high that he might proceed faster than he should … Now the door is open to this and will never close again. It’s like a hinge of history.”

Born to farmers in Hunan province in 1984, He has been described by his family and friends as fiercely driven and intelligent. In interviews with local media, he has said he would rather spend his holidays in the lab.

“He was always first in primary school, middle school, university and after that. He was never second. Always first,” his father told Beijing News. A former colleague of He’s told local media that the three words that best described the scientist were “smart, crazy and genius”.

“He is China’s Musk,” the colleague said, referring to the Tesla co-founder Elon Musk. Other media reports have called him China’s Einstein.

He, who also goes by his initials JK, depended on government and university scholarships to see him through university in China, where he studied physics. He then earned a PhD in physics at Rice University in the US and conducted post-doctoral research in genome sequencing at Stanford University.

He returned to China in 2012 as part of a talent recruitment programme in the technology hub of Shenzhen and because he wanted to improve Chinese research, which he believed was “weak”, according to his father.

He returned to a country that would soon be at the forefront of gene editing, using technology known as Crispr-Cas9.

China is one of few countries in the world known to have conducted tests on humans with Crispr. Since as early as 2015, cancer patients have been infused with cells of edited DNA. Beijing included gene editing as a key industry in its five-year science and technology development plan for 2016 to 2020.

Q&AWhat is Crispr?

Show

Crispr, or to give it its full name, Crispr-Cas9, allows scientists to precisely target and edit pieces of the genome. Crispr is a guide molecule made of RNA, that allows a specific site of interest on the DNA double helix to be targeted. The RNA molecule is attached to a bacterial enzyme called Cas9 that works like a pair of 'molecular scissors' to cut the DNA at the exact point required. This allows scientists to cut, paste and delete individual letters of genetic code.

In October 2020, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A Doudna were awarded the Nobel chemistry prize for their work on it – the first time that two women have shared the prize.

The UK and many other countries have outlawed the genetic modification of babies, which is considered unsafe and unethical because any modifications would affect the child’s offspring and future generations.

He used the technology to modify the gene CCR5, a doorway for HIV, in several embryos created through IVF for couples with HIV-positive fathers, presenting it as an HIV vaccine trial.

Chinese regulations have not kept pace with scientific breakthroughs in this area. The only relevant regulations come from an “ethics guidance” document released in 2003 that bars the use of any research embryos for reproduction. There are no specified punishments for such violations.

He was able to keep his work from much of the scientific community. He retrospectively registered the clinical trial with Chinese authorities in November, well after the work had been done. A researcher associated with the trial has reportedly said He did not inform all staff involved that his project involved gene editing.

“How can a scientific experiment with so many uncertainties be kept as a secret for such a long time?” asked He Kaiwen, a researcher at Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Biology and Chemistry in Shanghai, who was one of a group of more than 120 scientists who released a statement condemning He’s work. “This shows that there’s huge problem with the transparency of scientific research.”

She added: “This is a completely new situation. This question is one we have never faced before.”

The international scientific community continues to reel from He’s claims, which he defended at a global summit on the topic in Hong Kong on Wednesday. The organising committee of the conference, the International Summit on Human Genome Editing, called the scientist’s statements “unexpected and deeply disturbing” and recommended an independent assessment.

“Even if the modifications are verified, the procedure was irresponsible and failed to conform with international norms. Its flaws include an inadequate medical indication, a poorly designed study protocol, a failure to meet ethical standards for protecting the welfare of research subjects, and a lack of transparency in the development, review, and conduct of the clinical procedures,” the committee said in a statement on Thursday.

Officials from China’s national health commission promised on Thursday to “investigate and deal with any unlawful behaviour” by He.

The government-affiliated China Association for Science and Technology said the incident was “seriously damaging to the image and interests” of the Chinese science community and expressed its “indignation and condemnation of the people and institutions involved”.

Chinese scientists have called for comprehensive regulation to prevent this kind of research in the future. “The improvement of any law comes from exploration,” said He Kaiwen. “Something happens. It reveals a loophole, and we fix it. This is what we scientists want: to push the industry in the right direction.”

Additional reporting by Xueying Wang