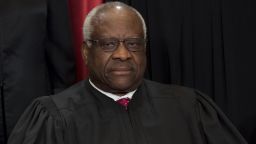

Justice Clarence Thomas issued a jaw-dropping opinion earlier this week when he suggested it was time for the Court to revisit a First Amendment precedent that some believe is a crown jewel of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.

Thomas targeted New York Times v. Sullivan, a 1964 opinion holding that public officials have a higher burden to prove libel.

“It’s one of the most important and consequential rulings in the history of our country,” said First Amendment expert and Supreme Court advocate Theodore J. Boutrous of Gibson Dunn.

The audacity of Thomas’ opinion, that was tucked into a related case, took Boutrous and others by surprise.

It even reignited a whispering campaign among progressives that the 70-year-old justice is preparing to retire. The thinking goes that he had launched the opinion – joined by no other justice – as a kind of last salvo as he prepared to relinquish his seat to a younger Trump nominee.

But those close to Thomas saw something entirely different.

For them, it was another opportunity for Thomas to plant seeds for the future in an area of law that he thinks deserves more attention.

They say the opinion was less of a last salvo and more the establishment of a new marker for a justice who believes in correcting what he sees as past mistakes, even if he speaks alone.

And while there may not be Justice Thomas tattoos, or tote bags, or other swag that surrounds Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and he may lack votes on the Court to win the day, after more than a quarter century on the bench, he has established a veritable army of former clerks and those he calls his “adopted clerks” who see the world and the law through a similar lens.

They find it hard to believe retirement rumors, especially now that Thomas sits with a recently solidified conservative majority, and in some ways is hitting a new stride.

New York Times v. Sullivan

In his opinion on Tuesday – which was technically a concurrence on a denial of cert for a speech related case – Thomas complained that under the Court’s First Amendment precedents, “public figures are barred from recovering damages for defamation unless they can show that the statement at issue was made with ‘actual malice’ – that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The rulings subject plaintiffs to an almost “impossible standard,” Thomas wrote, and that instead of “simply applying” the First Amendment as it was understood by the people who ratified it, the Court had drifted into the realm of policy and fashioned its own rule.

“We should not continue to reflexively apply this policy-driven approach to the Constitution,” he said.

His opinion is grounded in the judicial philosophy of originalism, a theory also championed by the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

But while Scalia in public speeches could be critical of New York Times v. Sullivan, he never wrote an opinion like Thomas’, perhaps out of respect for precedent.

Boutrous thinks if Thomas was laying down a marker, it was a dangerous one.

“If that view were to prevail, it would be a dramatic rupture in our democratic system because New York Times v. Sullivan stands for the basic principle that citizens should be able to speak without the fear of punishment in a civil case, especially when criticizing public figures and discussing issues of public importance,” he said.

Laying down markers

Supporters of Thomas, like conservative lawyer Charles J. Cooper, say that Tuesday’s opinion is an extension of his jurisprudence and reflects the fact that he has often shined a spotlight in an area of the law that troubles him.

“Thomas’ solitary concurring opinion in which he articulated familiar originalist concerns about the correctness of New York Times v. Sullivan, is of a piece with his jurisprudence throughout the last two decades,” Cooper said.

“There is simply no reason to doubt that Justice Thomas will continue to raise his concerns about the correctness of the court’s prior decisions, no matter how sacrosanct they may be in certain quarters,” Cooper added.

Cooper points to early opinions Thomas wrote targeting the constitutionality of the bureaucracy that is commonly referred to as the administrative state.

During the 2014-2015 term, Thomas authored three opinions on the issue.

For Thomas, when Congress delegates its powers to federal agencies it gives those agencies too much power with too little accountability. As Thomas put it in Department of Transportation v. Association of American Railroads, the fight is about “the proper division between legislative and executive powers.”

“An examination of the history of those powers reveals how far our modern separation-of-powers jurisprudence has departed from the original meaning of the Constitution,” he wrote.

In 2015, Cooper wrote for National Affairs magazine, “Only Justice Thomas has consistently questioned the constitutionality of the modern administrative state.”

Today, the issue has gained steam and become a flashpoint in Washington and an initiative of the Trump administration.

Indeed, a former Thomas clerk, Neomi Rao, serves as the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. It is a little-known entity within the Office of the White House Office of Management and Budget charged with ensuring that federal agencies follow the law and act consistently with the administration’s policies. In short, Rao serves as President Donald Trump’s czar for regulatory rollbacks.

She’s also a nominee for the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, a breeding ground for future justices.

Thomas’s army

Washington is currently filled with Thomas’ former clerks and disciples.

Trump has nominated 11 former Thomas clerks for the courts. People like Gregory Katsas, who served in the White House Counsel’s Office and now sits on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. And James C. Ho, a Trump nominee who sits on the Fifth Circuit.

There are former clerks in the White House Counsel’s Office including Deputy Counsel Patrick F. Philbin and Kate Comerford Todd who is lead on the judicial nominations process for White House Counsel Patrick Cipollone. Andrew Ferguson, another former clerk, was slated to join the White House team, but instead, filled an opening as nominations counsel for Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham.

There are also “honorary” clerks – those close to Thomas who never worked for him – such as Alex Azar who serves as the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Senator Mike Lee, R-Utah, who serves on the judiciary committee. Mark Paoletta who is general counsel of the Office of Management and Budget.

Jeff Wall, another clerk, is Principal Deputy Solicitor General of the United States, arguing cases before the Supreme Court and helping to navigate the administration’s appellate strategy.

And it’s not just those in government who are making a mark.

Carrie Severino serves as the Chief Counsel for the Judicial Crisis Network, a group dedicated to supporting Trump’s nominees. In December, her group launched a $1.5 million national cable and digital ad campaign aimed at confirming conservative judges.

William S. Consovoy, working in private practice – is currently in federal court in Boston challenging Harvard’s use of race in admissions plans. A total of five former Thomas clerks are working on the effort that could eventually make it to the Supreme Court and upend precedent.

To be sure, former clerks aren’t lock step with Thomas’ thinking, but the sheer number of Thomas’ clerks currently serving in the administration is unusual.

Which isn’t to say that Thomas has enough votes on the court for some of his opinions. But he is a prolific writer, even if he is alone, much like Justice William Rehnquist was before he became chief justice in the mid-1980s.

It’s nearly impossible to get into a justice’s head on the issue of retirement.

But one thing is clear: Thomas is writing with the future in mind.