Tensions over capital punishment are high at the Supreme Court. The most recent quarrel came in the wee hours of April 12, when the five conservative justices rankled the four liberals by giving the green light to Christopher Lee Price’s execution in Alabama. In an indignant dissent opening internal court politics to public view, Justice Stephen Breyer lamented the majority’s unwillingness to discuss the case in conference the next day. Ordinarily measured, Breyer wrote that the majority’s middle-of-the-night rebuff of Price (who sought a less-painful execution method) abandoned “basic principles of fairness.”

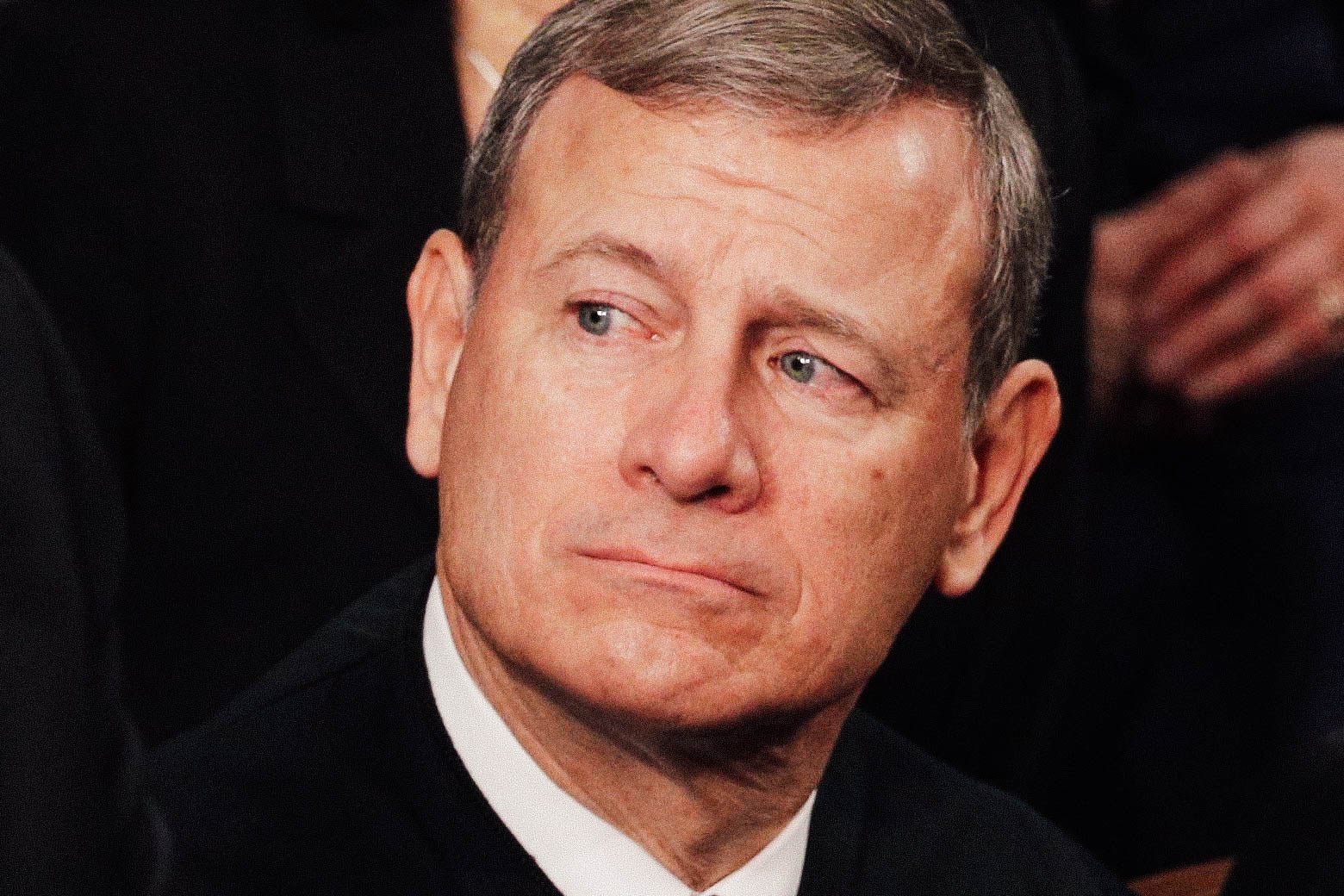

The razor-thin majority determining the fate of Price and several other death row inmates in recent months has been anchored—with deceptive quiet—by Chief Justice John Roberts. With Justice Anthony Kennedy now retired, Roberts is the new man in the middle. He isn’t the most enthusiastic cheerleader for the ultimate penalty on the court—that honor belongs to the trio of Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Clarence Thomas—and rarely flashes his cards in capital punishment cases. But his votes are shaping a newly savage jurisprudence.

Joan Biskupic’s The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts, a deeply researched new biography of the jurist, helps piece together Roberts’ approach to capital punishment cases. It includes a cautionary tale from 1981, when Roberts, then 26, was clerking for William Rehnquist—the man whom he would eventually succeed as the chief justice. In a death penalty appeal that year, then-Justice Rehnquist vented his frustration with criminals having “so many bites at the apple.” Long delays between conviction and execution, he wrote, make a “mockery of our criminal justice system.” Biskupic notes that Justice Lewis Powell privately told the chief justice his irascible solo opinion was “misguided”—an admonition that went unheeded. In 1990, Rehnquist would go on to lobby for a Republican bill drastically limiting appeals for capital convicts. Defying a judicial norm against entering the political fray, Rehnquist said the measure would fix a regime that “verges on the chaotic.”

Nineteen years later, there is little reason to think the new chief is any more tolerant of extended capital appeals than Rehnquist, whom Roberts replaced upon his death in 2005. But the 17th chief justice’s style and strategy are starkly different. Whereas Rehnquist had no compunction about writing testy capital punishment opinions, Roberts is a model of circumspection. During his 14 years at the helm, according to Adam Feldman of Empirical SCOTUS, Chief Justice Roberts has publicly dissented only four times from a decision to block an execution in response to a request for an emergency stay. In argued merits cases, he has kept his quill dry on all but a few occasions. In 18 death penalty rulings since 2005, he has chosen to write opinions only four times: one majority opinion (in a capital case outside the Eighth Amendment context), one plurality opinion (with two other justices), one concurrence, and one dissent.

Perhaps the chief justice’s most powerful role, when he is in the majority, is opinion assignment. So it is remarkable that only once, over a decade ago, did Roberts assign himself a substantive death penalty opinion. Since that 2008 foray in Baze v. Rees, a decision upholding lethal injection against a claim it is “cruel and unusual,” the chief has been happy to let his colleagues navigate the treacherous waters of the death penalty debate. He has assigned some opinions of the court to centrist justices like Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Anthony Kennedy. But he has passed off dissents from left-leaning rulings to his conservative colleagues, as in 2008’s Kennedy v. Louisiana (barring capital punishment for rape) and 2014’s Hall v. Florida (regarding standards for assessing a convict’s intellectual disability). Justice Alito wrote both of those dissents; Roberts joined them. And in pivotal 5–4 rulings favoring the conservatives, he has let firebrands Alito and Gorsuch take the lead in edging the court further to the right.

A recent tilt came at the start of April, when Gorsuch wrote a 5–4 opinion that shocked many for its callousness. A Missouri man with cavernous hemangioma, a rare medical condition, had asked the justices to switch his execution method from lethal injection to nitrogen gas. Lying on a gurney and being injected with a lethal drug cocktail, Russell Bucklew’s doctors explained, would cause tumors in his throat to burst, flooding his airway with blood and suffocating him. Gorsuch, writing for his four conservative brethren, did not just turn down Bucklew’s request—he repudiated him for waging a “headlong attack” on the court’s precedents and erected what Breyer properly called an “insurmountable hurdle” for inmates seeking a humane mechanism for their executions. The harsh overtones of Gorsuch’s opinion did not flow from Roberts’ pen. But the chief signed his name to the ruling.

Meanwhile, in a highly controversial pair of orders this year regarding an inmate’s right to clergy in the execution chamber, Roberts kept himself well out of the spotlight, taking advantage of the anonymity the court’s so-called shadow docket affords reticent justices. We know—because four justices noted their disagreement—that Roberts rejected a Muslim man’s right to an imam at his side in February despite the availability of a minister for Christian inmates. In an unsigned ruling, the majority offered a thin justification for the decision, which Kagan called “profoundly wrong.” When a Buddhist inmate came to the court with an identical claim in March, an apparently chastened majority granted it. Thomas and Gorsuch noted their disagreement with the court’s ruling in favor of the Buddhist man, and in a brief concurrence, Justice Brett Kavanaugh explained why he saw the Muslim and Buddhist inmates’ cases differently. But Alito and Roberts gave no indication of how they voted. Again, the chief kept himself safely under the radar.

Roberts does occasionally emerge from the shadows to broadcast a willingness to break with his fellow conservatives on death penalty cases. In February, he joined the Supreme Court’s liberal justices to give an inmate with dementia another chance to challenge his death sentence and chastised a Texas court for sending an intellectually disabled convict back to death row. But there is less than meets the eye in these leftward feints: Both cases simply involved the application of a precedent a lower court had ignored. Neither move should obscure the chief justice’s hard line on the death penalty evinced in hundreds of other votes. Indeed, when the court decided the precedents behind the two February cases 12 and two years ago, respectively, he was in dissent both times.

Shrewd moves by Chief Justice John Roberts in the death penalty docket seem to bear out Biskupic’s conclusion that—despite his self-description in his confirmation hearings as a judge who simply “call[s] balls and strikes”—Roberts “did not entirely shed his partisan thinking once he donned the black robe.” The Chief quotes Roberts’ statement that, as chief, he sometimes “sublimates” his conservative views. A better account of what he is up to, Biskupic finds—drawing on interviews with his colleagues—is “strategizing.” His cunning maneuvers over death penalty squabbles suggest she is right. While striving to keep up appearances as an honest broker, Roberts is discreetly deploying his new conservative majority to shore up America’s dwindling capital punishment regime and buttress its executioners.